We exit our car in a small parking lot on the north side of Manitou Springs, Colorado, and look up at the tall mountain to our west. Pikes Peak stands 7,795 above us on this sunny day, dominating the landscape here on the front range.

There are a multitude of different ways to get up this mountain. A paved road allows people to drive their cars right to the top. Or you can hike up a 13-mile long trail to get to the summit.

But today we’re taking the Broadmoor Manitou and Pikes Peak Cog Railway up an 8.9 mile long journey to the top.

We walk across the street to the train station and walk down a flight of stairs to get to the boarding platform.

Looking around on the platform, you would be forgiven to think that you’ve entered a portal right to Switzerland. The station replicates the type of historical alpine stations you would see in the Swiss Alps with red pointed roofs and blue siding and railings.

All you’re missing is polka music and some lederhosen.

And it makes sense. Switzerland contains the vast majority of the cog railways in the world, and Zalmon G. Simmons was inspired by the Swiss cog railways when building the line in the 1890s.

Today we’re one of a couple hundred people waiting to board the train. Even with two tracks and expanded infrastructure, the station and platform are packed to the brim with people headed up to the top of Pikes Peak.

Taking us up the mountain is a bright red diesel engine sitting on track one. Built by Stadler Rail in Switzerland, the engine and the three red coach cars that accompany it arrived on the railroad in 2021 just as the line finished its complete rebuild.

Trains on the Pikes Peak Cog Railway feature the engine on the downhill side of the train to push the train up the mountain and keep the cars contained on the downward trek. The configuration helps prevent the potential of a runaway train.

Finally, the doors open to the train 15 minutes before our scheduled departure. We walk in and hand the conductor our tickets and take our seats on the left side of the train.

The interior of the train is laid out in a 3+2 style seating arrangement. Our seats are on the 3 seat side of the train, which will give us a great view of the mountains once we get above the timberline.

At last the clock strikes the top of the hour and the doors close. The train lurches forward, and we begin our 8.9 mile, one hour journey to the top of Pikes Peak.

The mountain we’re climbing up today formed over a billion years ago.

Magma pushed up and out of the Earth’s crust and turned into granite over and over in a process called uplifting. The end result of the process, which also built a lot of the mountains in the state, was the dome-like mountain that stands before us today.

The first people to find what would be named Pikes Peak were the Mouache, the Caputa and the Tabeguache, nomadic bands of the Nuche tribe, known today as the Ute. They named the mountain Tavá Kaa-vi, or Sun Mountain. The Mouache lived on the eastern side while the Tabeguache lived on the western side and the Caputa on the southern side.

The indigenous tribes are thought to have arrived in the Pikes Peak region around 500 A.D., although Ute oral history says they were created there. As such, the mountain holds a sacred place in the tribe’s history.

Members of the Nuche tribe frequented the summit, and there are many sacred sites at various points at the mountain that are only known by the members of the tribe to protect them.

In the 1800s, members of the Arapaho tribe moved to Colorado and to the area near Tavá Kaa-vi and began to call the mountain Heey-otoyoo’, which means “long mountain”.

As a part of the American Indian wars in the late 1800s, members of the Nuche/Ute tribe were forced from the land they inhabited for at least 1300 years to reservations in southwest Colorado and southeast Utah.

The beginning portion of the ride lets us know that we are not on a normal train.

The grade is much, much steeper than any train we’ve been on before. In fact, it feels like we’re going up a very long lift hill at the start of a roller coaster rather than going on a simple train ride.

The average grade (or how high the train goes per section of track) for the line is 12 percent. That means for every 100 feet of track we travel, we’re gaining 12 feet. And at some points on the line, the grade is up to 25 percent. For reference, the steepest grades mainline trains tackle are four percent grades, and even those are super rare.

In fact, the 12 percent average grade would be way too steep for a normal train to travel up the mountain. So instead, the Pikes Peak Cog Railway is not a normal train; it’s a cog wheel train.

In addition to the two main rails, a cog railway introduces a rack in the middle. The teeth in the rack lineup with the teeth in the cog (where the name cog railway comes from) underneath the train. The cog and rack rail are what allow the train to climb up the mountain and safely return down to the base easily.

While cog railways are numerous in the Swiss Alps, and are what inspired this cog railway, the Pikes Peak Cog Railway is one of only three in the United States; the others being on Mount Washington in New Hampshire and the Quincy and Torch Lake Cog Railway in Hancock, Michigan.

After passing through the yard where the trains are stored and worked on, we enter into the forest. We start our journey by running alongside Ruxton Creek. The creek introduces us to several different interesting formations on our journey.

The first is a near perfect diamond shaped boulder off to the right side of the train. Then a small waterfall. After crossing the creek, we come across Minnehaha Falls, the highest waterfall in North America (yes, technically higher but not taller than Niagra Falls).

Before long we pass another train that’s stopped in a siding on the way down back to Manitou Springs to let us pass. This is one of several new sidings on the line allowing the railroad to run as many trains as possible to keep up with the demand. Trains headed up the mountain generally have the right of way while descending trains have to wait.

After passing the other train, we come across the site of the Halfway House Hotel. In the early days of the railroad, trains would stop here to allow passengers to have a lovely picnic. The hotel started as a small cabin built by Thomas Palsgrove which then turned into a 22-room hotel.

The city of Colorado Springs bought the property in 1916, and in 1925 the city tore down the hotel for a new reservoir. Today, the train continues past this location and continued up the steep grade as we near the halfway point on the line.

Through a rare break through the trees, we can a quick glimpse of Colorado Springs, the purple mountains majesty and amber waves of grain.

As we begin to climb above the timberline, we begin to see the scene that inspired Katherine Lee Bates to write the words that would eventually become America the Beautiful.

Bates took a train trip across the country to begin teaching at Colorado College in 1893. Along the way she noted the different scenes and landscapes she saw across the country. While those scenes eventually found their way into the poem, it was the trip up to the summit of Pikes Peak on the back of a mule that would lead to the inspiration to start the writing process.

She began writing down the words when she got back to her hotel, and two years later the poem was published in the Congregationalist to commemorate the Fourth of July. In 1904, Bates published an amended version of the poem, which, among other changes, removed the “America, America! God shed His grace on thee” section of each verse.

Meanwhile, the first known melody written for the song was sent in by Silas Pratt when the poem was published in The Congregationalist, the first of 75 different melodies written for the song by 1900.

The version that we know today was composed in 1882 by Samuel A. Ward, the organist and choir director at Grace Church, Newark. Like Bates, Ward was inspired to create the melody by his own trip. The tune came to him on a ferry boat ride from Coney Island back to New York City, and he began building the song upon returning home.

Ward’s music combined with Bates’s poem were first published together in 1910 and titled “America the Beautiful” with the words we know today.

And the song quickly became a hit.

The tune was a candidate to be the national anthem of the U.S., but was passed over in favor of the Star Spangled Banner. There have been efforts to make it a national hymn or an additional national anthem, especially by the Kennedy administration, but those efforts have failed so far.

Still, it’s a terrific song that paints a picture of the country. And it all started right here on this mountain.

As our climb continues, we start to notice breaks in the trees, giving us a better view of the plains below. We can start to see Colorado Springs and the contrasting flat land to its east and beyond.

We can also see Lake Moraine just below us. This man-made lake is one of several reservoirs in the area that the city of Colorado Springs manages to supply the town and surrounding communities with water. The reservoirs collect water from the melting snow and release the water downstream for use by people.

Some reservoirs, like North Catamount Reservoir and Crystal Creek Reservoir to the north of the mountain, are easily accessible and host a number of recreational activities like kayaking. But Lake Moraine can only be accessed by a single dirt road that’s blocked for public access. So instead, we get to enjoy the view of this peaceful lake.

Beyond the lake is Almagre Mountain. Standing at 12,360 feet, this mountain’s peak is the only other mountain peak over the timberline that can be seen from the city of Colorado Springs. While there are no roads to the top of that mountain, you can hike to the top to get stunning views of the entire front range in central Colorado.

As we continue to climb up, we notice clouds starting to move in and try to surround us. The summer months are the rainy season for this area. While most mornings start with a crystal clear sky, by afternoon rain and storms can start to move in.

But those are a problem for a little bit later on the trip. For now we continue to enjoy the beauty of the view and nature on our trip. And reaching 10,000 feet in elevation, we have quite the view of the surrounding area.

Among the European settlers to find the mountain, the Spanish were the first in the 1700s.

But the first American expedition to the peak was in 1806 when Zebulon Pike led his team to attempt to climb the mountain. The expedition got up to the timberline roughly halfway up the mountain, but with the wrong clothes for the deep snow and cold weather and the inability to find animals to kill and eat, Pike and the team abandoned the ascent.

Still, the mountain now bears his name in the United States.

Edwin James became the first European settler to reach the summit of Pikes Peak in 1820. Originally traveling as a backup botanist on an expedition to the area, the mountain stood out to him as they traveled across the plains to the east.

When they arrived in the region, James and others left the team to try to summit the mountain. The group succeeded, and James also discovered blue columbine, which today is Colorado’s state flower.

Pikes Peak really took off with the start of the Pikes Peak Gold Rush in the late 1850s.

While gold had been found in other parts of the state first, the name came from the fact that traveling prospectors from the west would see the peak for miles and miles as they approached the Rocky Mountains. The rush bolstered the state’s population and helped Colorado become a state on August 1, 1876.

Gold was finally found in the Pikes Peak region in 1893 around the Cripple Creek area to the southwest of the peak, leading to one of the final last gold rushes in the lower 48 states.

Today, Pikes Peak attracts thousands of tourists who ascend the mountain via the toll road, cog railway or hiking up one of the two trails.

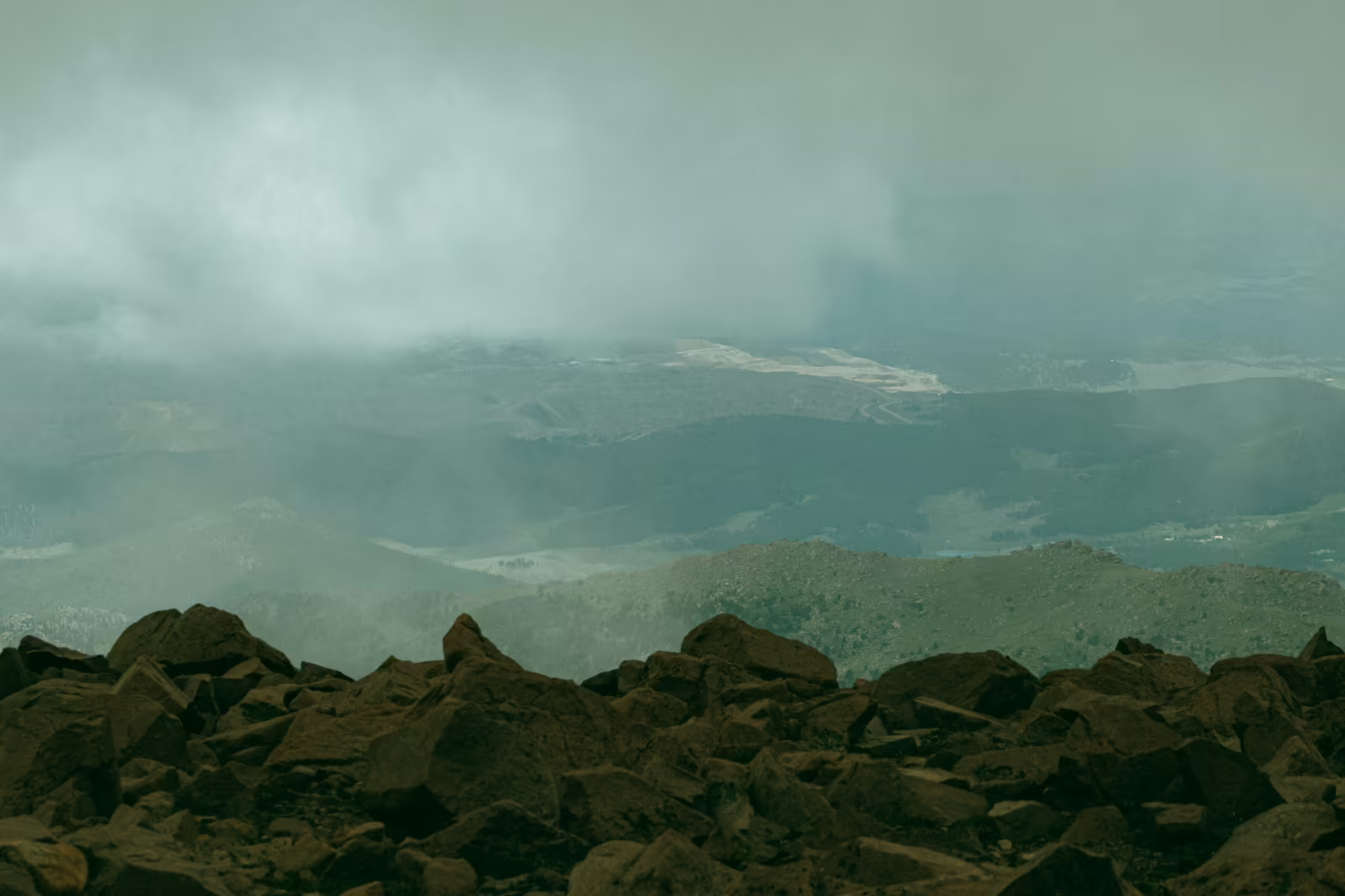

Emerging from the timberline at 11,700 feet, we get a completely unobstructed view of the land around us.

No longer dodging in and out of trees, instead we have grassland beneath us. That coupled with the clouds scrapping along the ground could easily fool anyone to thinking we might be in Scotland rather than Colorado.

The grade also starts to get steeper too as we inch near the summit. The cogs are doing all they can to drag this train up to the top of the mountain, something no ordinary train could do.

As we straggle along, we notice the terrain again changing. The grassland is starting to give way to moss and teeth distinctive pink Pikes Peak granite rocks beneath us.

The air is also starting to change. Now firmly above 10,000 feet, the lessening air pressure means less oxygen is getting into our bodies. We’re fine sitting down on the train right now, but we’ll definitely feel the change when we walk around the summit in a few minutes.

To our southwest we can just make out the town of Cripple Creek. Founded in 1892 as one of the first towns in the state, Cripple Creek almost became the state capital for Colorado.

The town grew almost exponentially after its founding thanks to the Pikes Peak Gold Rush and gold deposits found in the area. In its first three years of existence, it went from a population of 500 to 10,000. You couldn’t get a room at the Palace or Windsor Hotels, but you could rent a chair for $1.

By the time all was said and done, over $500 million worth of gold ore was mined from the area.

But like all boom towns, it wasn’t meant to last.

Two fires in less than a week in 1896 destroyed much of the town. While a lot of it was eventually rebuilt with better material, the damage was done. Denver and the cities along the front range grew bigger and became the economic driver for the state.

We’ve almost reached the top of the mountain. We ride along the saddle back, giving us a view in either direction, although increasing clouds start to block our view of the area below.

To our west we can start to see cars coming up the Pikes Peak Toll Road towards the summit.

After riding along a few more steep grades, we ease on into the station at the top of Pikes Peak, 14,115 above sea level.

The idea for the railroad came in 1888 by inventor Zalmon G. Simmons.

Simmons, who founded the Simmons Bedding Company, was a part of a team that was surveying a route for a telegraph line through Englemann Canyon and up to the top of the mountain. The trip was slow and miserable for the team and led Simmons to wonder if there was a better way to get people to the top of the mountain.

The answer was a cog wheel railway that could tackle the steep grades up the mountain. Simmons started his new railway in the small town of Manitou Springs nestled at the bottom of the mountain and surveyed a way up.

Construction started in 1889 with construction crews consisting mostly of Italians using pickaxes and donkeys to help build the 8.9 mile route to the summit.

Surprisingly, the first train on the line ran a year later, going up to the Halfway House Hotel halfway up the line. And on June 30, 1891, the first train traveled to the summit, opening up the summit to anyone.

The first trains up the mountain were pushed by steam engines, but the railway began moving to diesel engines in 1938 and phasing out their old locomotives. One of the original steam engines as well as an old car can be found on display at the Colorado Railroad Museum in Golden, Colorado.

The railway proved to be a smashing success as the public clambered aboard to get to the top of the mountain. In the 1970s, the line purchased larger train sets with more capacity to handle the growing crowds.

As the calendar flipped to the new millennium, problems began to arise on the line. Maintenance workers began to notice that the cogs on the train, a crucial piece to get trains up the mountain and prevent runaway trains, were wearing out at a much faster rate than before.

The line closed in October 2017 to allow crews to try to fix the problem, but found that only a total rebuild of the line would completely solve the issue.

In 2019, the line began a complete overhaul. The original rails laid in 1889 were pulled up and replaced with stronger and better rails, the station in Manitou Springs was refurbished and a completely new summit house was built to better accommodate both train passengers as well as hikers and tourists traveling up the toll road.

The overhaul finished in May 2021, allowing us and many, many, many other tourists a spectacular ride up and down the side of Pikes Peak.

We finally arrive at the summit of Pikes Peak and exit the train.

The air is considerably colder than it was back in Manitou Springs. In fact, as the clouds envelop us at the summit, we can see small snowflakes fall around us and some snow still on the ground from the winter snowfalls.

Unfortunately, the clouds also block our view to the east. From a point just above the railroad, we should be able to see Colorado Springs below with Denver off to our north, northeast by 65 miles and, if it’s a really clear day, all the way to the Kansas border 162 miles away.

Instead, we’re greeted by the fog of the clouds.

Turning to our left and moving west across the summit, we see a bit of hope — a break in the clouds and a view of the western side of the mountains.

From this vantage point, we can see just how wide and deep the Rocky Mountains are. Pikes Peak is just the first of several waves of mountains as you trek west across the state. The mountain peaks appear to go on for miles to the west.

We also have a great view of the Collegiate Mountains about 60 miles away towering above the town of Americus. The name comes from the three main peaks that make up this portion of the Rocky Mountains: Harvard, Yale and Princeton.

Together, they are three of the 25 mountains that stand above 14,000 feet in the state of Colorado, the most of any of the lower 48 states.

As other tourists on the summit take selfies and panoramas of the landscape, we continue walking counterclockwise across the summit. The air is thinner up here, and the altitude sickness is starting to catch up with us flatlanders.

As we approach the southwestern point of the summit, we see a road arriving at the top. This is the Pikes Peak Toll Road, which travels from just north of Manitou Springs along the side of the mountain up here to the summit. The road also features a number of different pull out points along the way where folks can stop and take in the view around them.

It’s also home to one of the most famous road races in the world: the Pike Peak International Hill Climb. Held in June each year, the hill climb sees drivers compete against each other to race the 12.42 miles to the top while climbing up 4,720 feet.

The race, which started in 1916, is held in a time trial format, but with 156 turns and nearly no guardrails, the thrill comes from watching the drivers race the road itself in addition to the other competitors. Surprisingly, there have only been seven deaths in the history of the event despite several steep drop offs that drivers have to navigate.

Frenchman Romain Dumas currently holds the record for the fastest ascent of the mountain, finishing the course in 7 minutes and 57 seconds in 2018 in his Volkswagen I.D. R.

Today, cars are coming up and down the mountain at much, much lower speeds thankfully.

The Rocky Mountains have always been an obstacle for humans and animals trying to cross over to the other side of the continent.

Stretching from the northern border of British Columbia down to Northern New Mexico, the mountains divided Canada and the U.S. for a long time. While Lewis and Clark navigated the mountain range in 1805 through what is today Montana and Idaho, regular movement across the Continental Divide did not happen at a large scale.

On July 24, 1832, Benjamin Bonneville led the first wagon train across the Rocky Mountains by using South Pass in the present state of Wyoming, starting migration to the Pacific Northwest.

The Oregon Treaty of 1846 with Britain opened up the northwest corner of the country and started the Oregon Trail with travelers traversing the Rocky Mountains in Wyoming, Utah and Idaho in the late 1840s.

But even after the U.S. won the Mexican American War in 1848 and completed its westward expansion to the Pacific coast, it was still easier for folks to take a boat and sail around South America instead of traveling overland through the Rocky and Sierra Mountains.

That is until the golden spike was drilled on the first transcontinental railroad in Promontory Point, Utah in 1869. The line now connected both coasts together for the first time and made travel between east and west super easy.

No longer would someone need to be a part of a wagon train or take a long stagecoach ride to get between Sacramento and Chicago. Instead, they could just book a train ticket, sit back and enjoy the ride.

In 1885, Canada connected its east and west cities with its own transcontinental railroad.

As the main transportation mode changed from trains to cars at the turn of the century, roads would need to be built to move people through the mountains in both directions.

The Lincoln Highway was one of the first transcontinental roads to be built in 1913. Now known primarily as U.S. Route 30, the road traveled through New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, Nebraska, Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, Nevada and California, allowing motorists to start at the Atlantic Ocean and finish the trip at the Pacific Ocean.

And, in more modern times, the last part of the interstate system was completed in 1992, connecting the original ending point in Denver to Interstate 15 in Fort Cove, Utah. This section of interstate is considered an engineering marvel, with hanging roadway through the narrow Glenwood Canyon on the west side of the mountains and Eisenhower tunnel, the highest interstate tunnel in the country.

The end result is much easier travel for everyone over the continental divide.

Before we board the train to head back down the mountain, we make a stop in the new summit house for a quick pitstop. In addition to restrooms, the summit house also holds a cafe for folks to grab a bite to eat and a gift shop for souvenirs.

Unfortunately, we see that there are long lines for both as we walk down the steps. I guess we won’t be getting a donut or a pin today.

Still, what’s here is much better than what had been here before.

Outside we can see the remains of the old summit house. It was a simple stone building the size of a house with a small cafe. I can’t imagine trying to squeeze a train full of people plus car travelers in there.

Thankfully, the city of Colorado Springs built this brand new summit house when the cog railway was rebuilt in 2021, giving all of us a much better experience.

As the departure time for our train back down the mountain nears, we head outside. There we see the next train heading up the mountain crawl to a stop at the station with another trainload of people who will be exploring the summit.

We board our train, and in a few minutes we’re headed back down towards Manitou Springs.

The view on the ride down is just as great as the ride up, although there seems to be more clouds than before.

As we creep closer to the timberline and 10,000 feet, we also notice our altitude sickness starting to go away. The amount of oxygen is slowly starting to increase and it’s easier to catch our breath.

Right before we reach the timberline, we sneak in one final glimpse of Colorado Springs below right underneath the clouds. And then we’re back in the forest.

This time, we’re the ones stopping in the sidings to let uphill trains pass. Fortunately, everyone is running on time today as we don’t have to stop for too long before the uphill trains pass by.

We start to pass the familiar landmarks we saw on our climb up the mountain. We pass where the Halfway House Hotel used to stand. The train slowly climbs down the 25 percent grade, the cogs and brakes keeping this from turning into an impromptu roller coaster ride.

We travel pass the waterfalls, down through Engelman Canyon and, finally, back past the yard and into the station in Manitou Springs.

We’re in no rush to leave this incredible experience, so we let others get off the train before we finally disembark. We exit onto the platform and then head back up the steps out of the station and into the car.

We climbed a mountain today.

Get the Entire Gallery

Pikes Peak offers travelers an amazing view of the Rocky Mountains to the west and Colorado Springs the plains of eastern Colorado to the east. Now you can take home those amazing views right from the comfort of your home for your website, your home, your business or wherever else you want to show them. Just check out the photo gallery below and select the photos you want or get the entire gallery for just one easy price!